19 Artworks challenge the Old Masters

19 Artworks challenge the Old Masters

The collections of the Kunsthistorisches Museum run the gamut of five millennia of art history – from Ancient Egypt to the turn of the eighteenth century. For a few months, this history will be continued: 19 carefully selected modern and contemporary artworks encounter Old Masters – the oldest painting dates from 1842, the youngest was especially created for this exhibition in 2018.

Old Ideas are relevant for Modern Art

The younger works help lead visitors from where our collections end to artworks being produced today. The idea is not a complete history of the art of the previous two centuries but to change our perception of Old Masters and illustrate their relevance for modern sensibilities and conceptions.

The enigmatic Connections between Influence, Talent and Chance

Curated by Jasper Sharp, the first group exhibition of modern and contemporary art at the Kunsthistorisches Museum explores the trans-cultural development of ideas and images over the centuries and reveals the enigmatic connections between influence, talent and chance. Visitors can join this dialogue of artefacts and discover in these confrontations conceptual, thematic or formal affinities that will forever change the way they see both the Picture Gallery and modern art.

Why Modern Art needs Old Masters

For the special exhibition »The Shape of Time« we open the Picture Gallery to facilitate exceptional encounters – like those between an ancient Roman sculpture of a young man and Paul Cézanne (1839-1909) that you see at the top of this page.

»The aim of the historian, regardless of his speciality in erudition, is to portray time.«

George Kubler, 1962

George Kubler's »The Shape of Time« as Inspiration

»If you want to understand modern art, read this!«

The title of the exhibition is taken from the book “The Shape of Time”, which was published by the American art historian George Kubler in 1962 and has influenced generations of artists and art historians.

For Kubler history is a process in which an increase of our factual and sensory knowledge is paralleled by repetition and renewal. He rejects the idea that art history is a series of unassailable facts or styles of clearly defined periods; for him, art is the visual manifestation of a continuous conversation through time: as a series of solutions that are the result of shared problems.

Kubler believed that »the anonymous mural painters of Herculaneum and Boscoreale connect with those of the seventeenth century and with Cézanne«. The exhibition »The Shape of Time« invites visitors to explore the connection between the past and the present – by observing, comparing and speculating.

The art critic and author Jennifer Higgie provided a summary of George Kubler’s »The Shape of Time«.

Jennifer Higgie is from Australia and is co-editor of the London-based contemporary arts magazine, Frieze. In her work as an art critic, Higgie focuses on contemporary art. Higgie has also published a number of novels and plays.

Why are you looking at me like that?

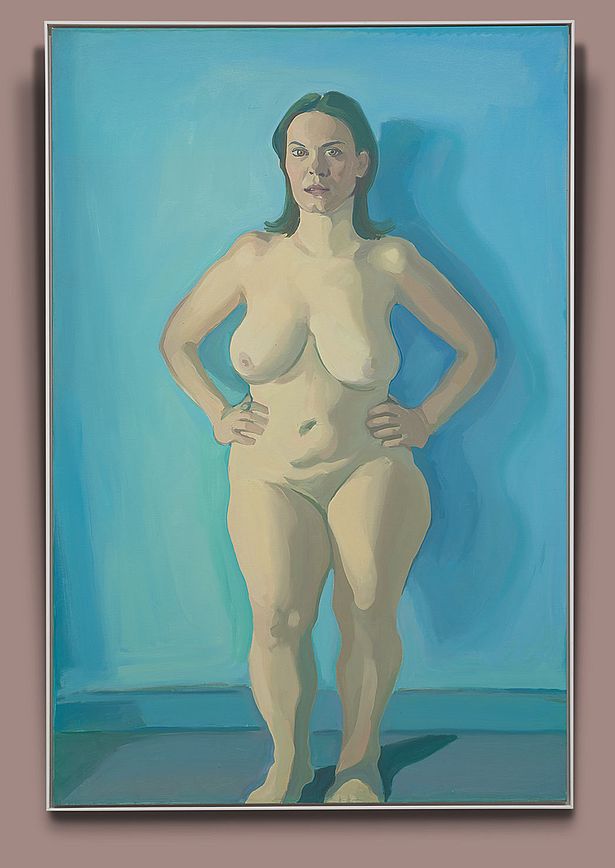

In this intimate scene, bashful Helena is facing the viewer – no, not you but her husband Rubens. Lassnig’s Iris is three centuries younger and her gaze is ironic, almost self-assertive. Both artists use the female body of their model for self-reflection in which both Helena and Iris move between personification and person: one is the ideal of love and beauty made flesh, the other the epitome of the liberated, completely autonomous woman in the US in the late 1960s.

Ben Street on »Rubens meets Lassnig«

By the time he had reached his early fifties, Peter Paul Rubens was perhaps the most celebrated artist in Western Europe. Endlessly inventive, erudite and skilful, Rubens was called upon to make paintings for churches and palaces in Italy, Flanders, England, France and Spain. By 1630, as he entered the final decade of his life, he had no need to seek out new patrons, and his work entered a more mellow and reflective period, epitomized by this painting of his second wife, Helena Fourment. This is Rubens in private mode, relishing in the folds of his young wife’s flesh, her dimpled knees, and her radiant complexion. The intimacy of the painting is borne out by its afterlife: it was the only one of Rubens’ works specifically left to Helena in the artist’s will, with the express request that it not be sold on. Helena is painted as though caught off guard, not quite able to cover her nakedness with the fur partially draped across her body. More than an erotic moment shared between newlyweds, the gesture is an allusion to the Venus Pudica, the classical sculpture of the goddess of love and beauty much alluded to in paintings of the period.

Maria Lassnig’s painting Iris Standing depicts the artist’s then neighbour, Iris Vaughan. Lassnig moved to New York from her native Vienna in 1968 to be, as she put it, »in the country of strong women«. Iris was a twenty-six year old part-time waitress, recently divorced, whom Lassnig both painted and filmed in a number of works. Lit by natural daylight from a hidden window, Iris meets our gaze with a steady and somewhat ironical expression, her lips slightly parted, as though captured mid-speech. Hands on hips, her assertive posture represents a challenge to the viewer, and perhaps an awareness of the painting’s startling force.

Here, as in her well-known self-portraits exploring »body awareness« – images of the figure that evoke its traumas and trials, rather than its likeness –, Lassnig finds within the ancient practice of figure painting the material to explore new conceptions of personal identity. Iris, raised in a strict Catholic family, found personal liberation in her divorce, and this painting embodies her renewed, or new-found, autonomy. Though shown with a fuller figure than she actually had, Iris presents herself as unadorned, liberated and utterly self-possessed.

Both paintings hinge upon the relationship between artist and model. There is no mistaking the nature of Helena’s gaze, as her expressively large eyes watch her husband watching her: this is a representation of the pleasure of being watched (regardless of how she in fact felt about posing for this painting). Iris, by contrast, stares back at this eccentric Austrian artist, almost staring her down, determined to maintain the posture, to possess her own image. In each case, the bodies of the sitters act as vehicles for the artists’ own self-reflexive thought. For Rubens, the body of Helena personified the ideals of love and beauty for which his paintings had always strained. The real and the ideal are harmoniously reconciled in her living, breathing divinity. Lassnig’s Iris is the epitome of the personal empowerment the artist sought in the culture of late sixties America: she, too, is somewhere between personification and person.

Ben Street

What do we have in common?

The two paintings share more than their sombre palette. Rembrandt’s self-portrait and Rothko’s flat portrait bear witness to both artists’ radical approach, their love of experimenting and their refusal to bow to contemporary popular taste. Throughout his life Rothko was fascinated by Rembrandt’s use of light to express a wealth of emotions from hope to desperation. Both focus on the conditio humana, the human condition, in their works and believe in the power of art – whether representational or abstract.

Jasper Sharp on »Rembrandt meets Rothko«

As a young man enrolled in classes at the Art Students League in New York, Mark Rothko was a frequent visitor to the city’s galleries and museums. He spent many hours in the halls of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with its unparalleled holdings of Old Masters. The artist towards whom he was first drawn was Paul Cézanne. From there he moved on to the great Italian masters, Giotto and Michelangelo, both of whom would shape the development of his work. Eventually, he arrived at Rembrandt, an artist who would be an almost constant presence in Rothko’s life. Among the works that he would have seen was a 1660 self-portrait that had been donated to the museum a decade earlier.

Rothko’s interest in Rembrandt focused as much on the artist’s subject matter and technique as it did on the effects that they would have on the viewer: put simply, the drama of the human condition. He was fascinated by Rembrandt’s handling of light as a vehicle to express a swathe of emotions from hope to despair. »Light makes it possible«, Rothko wrote, »[to express] a new factor that we can call emotionality…. [It introduces] humanity into the picture, an attempt to relate the representation of the individual emotionality in the terms of universal emotions.« It was as much the light from external sources that interested him as the light that illuminates Rembrandt’s paintings from within.

When Rothko was invited to teach a course on contemporary art at Brooklyn College in the early 1950s, he decided that it should begin with Rembrandt. A deliberate provocation, this decision was based in part on Rothko’s belief that the Dutch master represented the first time an artist had painted whatever he felt like doing. »Even before the days of the camera,« he had stated in a 1943 radio broadcast, »there was a definite distinction between portraits which served as historical or family memorials and portraits that were works of art. Rembrandt knew the difference; for, once he insisted upon painting works of art, he lost all his patrons.… There is, however, a profound reason for the persistence of the word “portrait” because the real essence of the great portraiture of all time is the artist’s eternal interest in the human figure, character and emotions – in short, in the human drama. That Rembrandt expressed it by posing a sitter is irrelevant. We do not know the sitter but we are intensely aware of the drama.«

At around the time that he made Untitled (1959/60), Rothko made several visits to the Metropolitan Museum specifically to see their collection of late works by Rembrandt. He cared deeply about his place in the continuum of art history. »Rembrandt and Rothko«, a friend of his recalls the artist once saying – before pausing, smiling, and trying it the other way round: »Rothko and Rembrandt«. Both artists were restlessly experimental, risk takers who refused to submit to popular taste. What they shared was a belief in the power of art – abstract or representational – to shape human experience.

Jasper Sharp

When do you take a bath?

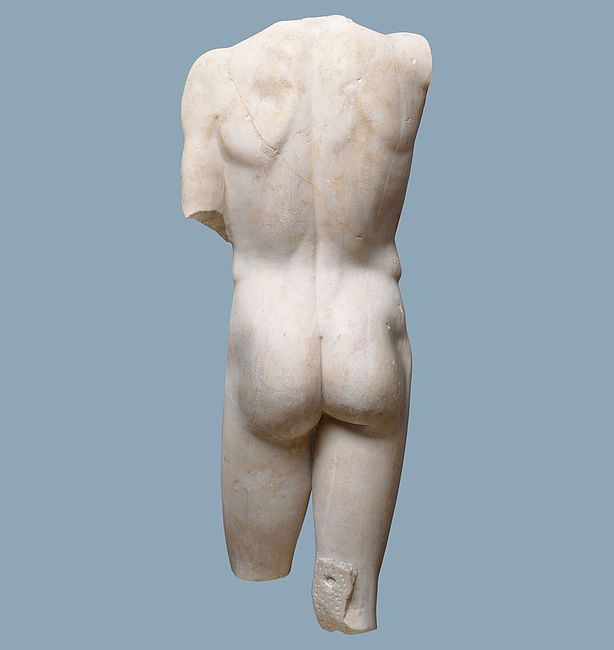

From the 1870s until the end of his life Cézanne repeatedly returned to the motif of bathers. In paintings such as this one from the 1890s (now in the Musée d’Orsay) he focuses on people and their connection to surrounding nature. We do not know who these bathers are, where they are, or in which century they live(d). But the rigid, classic composition clearly illustrates Cézanne’s debt to antiquity: he relied on sketches of classical sculptures for his depiction of bodies rather than work with real models. His figures seem both ancient and modern, creating a timeless image of man, just like the torso in the Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

Jasper Sharp on »Roman Antiquity Antike meets Cézanne«

»The Louvre«, Paul Cézanne said, »is the book from which we learn to read.« The French painter, one of the principal architects of modern art, spent many hours in the halls and galleries of the Parisian museum. He looked at the great paintings of the past, but also – crucially for the developments that he would set in motion – at sculpture. Over the course of his life, from student to old age, he filled sketchbook after sketchbook with drawings made directly from the museum’s collection of classical Greek masterpieces and their Roman copies.

Cézanne was more knowledgeable about the culture and history of the ancient world than any artist of his generation. He was most interested in the antiquity of Provence, where he spent most of his life. He learnt about its art, architecture and literature as a young man at the Collège Bourbon in Aix-en-Provence, where he studied alongside Émile Zola. During his studies, he enrolled at the town’s free municipal school of drawing (today the Musée Granet), where he would produce his first figure studies from life.

From the 1870s until the end of his life, Cézanne returned time and again to the subject of bathers, both male and female. His ambition, he stated, was to achieve a seamless integration of human figure and landscape. »[Cézanne] was moving towards the abstraction of natural bodies,« the avant-garde Russian painter Kazimir Malevich later commented, »because he saw in them only surfaces and pictorial volumes.« The works have a very carefully considered structure; in the case of Bathers (c.1890), it is a triangular, pedimental architecture formed through the four large figures in the foreground, which anchors the painting compositionally and gives it a distinctly classical feel.

Cézanne usually worked without models, relying instead on his sketches of classical sculpture to develop the positioning of his figures. In such works he is knowingly engaging with the history of art, from the subject matter itself, as made famous by artists such as Titian, Poussin or Peter Paul Rubens, to specific details such as the drapery, which makes reference to the Italian Renaissance. However, while the painting has deep roots in the past, it is hard to place its inhabitants within any specific moment in time, or indeed any particular place. They are at once ancient and modern. This sense of ambiguity is what makes the painting so remarkable, and undeniably contemporary.

Jasper Sharp

How long will you love me?

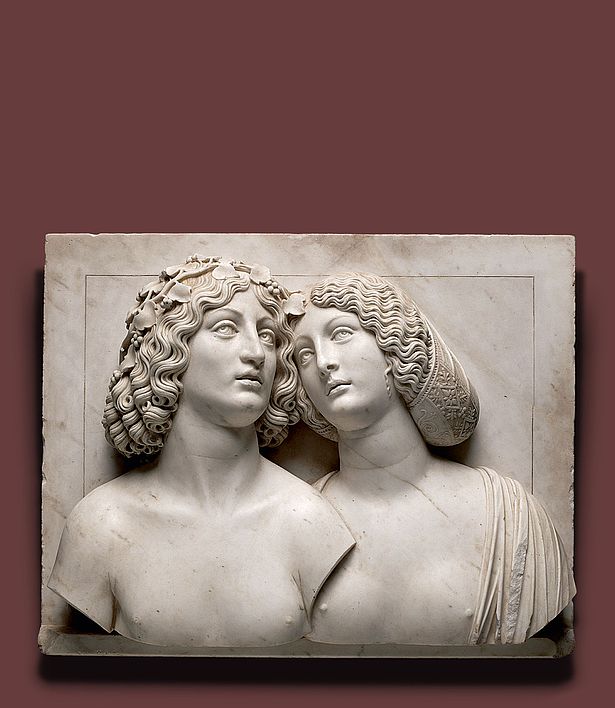

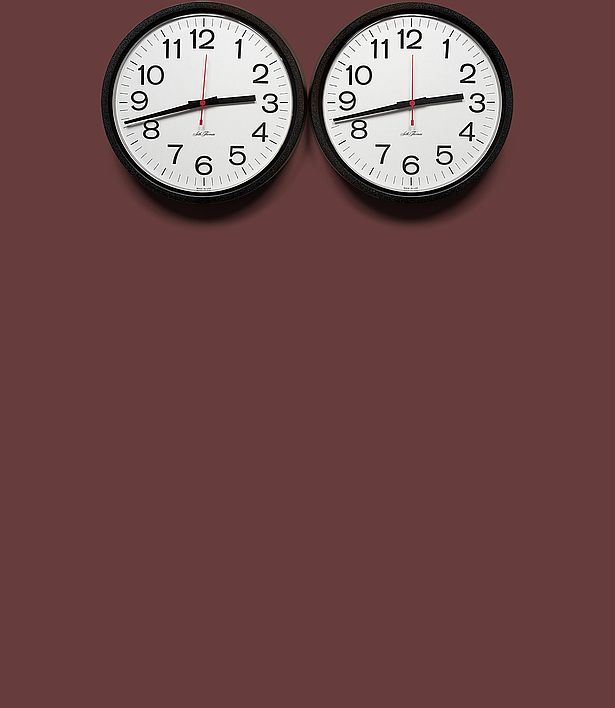

The faces of two lovers, their tenderly inclined heads touching gently, and two ordinary wall clocks whose seconds hands move in perfect unison: almost five centuries separate these two artworks but they have a lot to say to each other. Both Lombardo’s sculpture A Young Couple, 1505-1510, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s installation »Untitled« (Perfect Lovers), 1987–90, speak of love and transience.

Ben Street on »Lombardo meets Gonzalez-Torres«

Tullio Lombardo, Venice’s pre-eminent sculptor of the turn of the sixteenth century, did not achieve the posthumous celebrity of his painter contemporaries Giovanni Bellini and Titian, but his oeuvre shares their work’s archetypally Venetian wistfulness, which often borders on melancholy. In this relief sculpture, made around 1505, the young couple’s heads touch gently as they gaze upwards, both sets of their lips slightly parted. Their expressions are at once sensually languid and somewhat doleful. This mournful quality might be accounted for by the allusion to the Roman god of wine, Bacchus, in the vine leaves woven into the young man’s hair. Bacchus and his mortal wife Ariadne – to whom his female companion might, by her posture, be said to allude – were often represented in Roman funerary art, where the sleeping Ariadne represented the human soul, soon to be woken to eternal life. However, as the sculpture’s original patron is not known, we cannot be sure that such an allusion was indeed intended. Whether the sculpture alludes to marriage or the afterlife – or, perhaps and not unusually, both at the same time –, it is likely to have been commissioned by a humanist patron, perhaps a collector of antique statuary, to whose aesthetic the sculpture clearly nods. The dreamy romanticism of the sculpture, emphasised by its striking intimacy, seems suffused with the anticipation of a future life together, as well as the melancholic foreknowledge of that life’s eventual end.

The Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres chose two ordinary clocks and placed them side-by-side, just touching, for his work »Untitled« (Perfect Lovers). Gonzalez-Torres made a deliberate choice of clocks without any particular aesthetic appeal

This strategy builds on the Duchampian tradition of ordinary objects placed within a gallery and thereby lent a new context for thought. These two clocks, redolent of those on office or classroom walls, were chosen in part for their absolute distance from conventional standards of beauty. Here, Gonzalez-Torres illuminates the poetry of the overlooked: he turns seeing into looking. The batteries that power each clock are inserted simultaneously, and the clocks are set in synchrony, yet the naturally uneven lifespan of the batteries means that one clock will stop before the other. Gonzalez-Torres’ partner Ross Laycock died of an AIDS-related illness in 1991, and many of the artist’s works can be read as elegies to that lost love. The clocks’ ticking is like a heartbeat. Their direct allusion to time slipping away makes the work a contemporary memento mori, a reminder of death.

In both artists’ conceits on the nature of love and death, the two faces are at the same time identical and not: the touches of specificity (the grapevine, the snood, the slight discontinuity of the clocks’ hands) remind us that a couple is a harmony built of difference. The faces of the clocks and the faces of the sitters reflect each other: a human face is like a clock, its minutes counting down before your eyes. The trick of seeming eternal, whether it’s the continual sweep of the hands of the clock or the convincing realism of the loved one’s face – they might never change – is a reassuring lie told by works of art. The clocks might not stop, although we know they must.

Ben Street

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, »Madonna of the Rosary«, um 1601 © KHM-Museumsverband; Franz West, »Liege (Caravaggio)«, 1989, PPrivate collection, Vienna; Franz West, »Liege (Caravaggio)«, 1989, Musée d’Art, Toulon (France) © Archiv Franz West

We invite you. You get involved.

The exhibition invites you to take the stage: surrounded by these works you become a protagonist, a key player who exposes him- or herself to irritation, and through your observations and comparisons you enter into a very personal dialogue with the artworks.

19 generations-spanning Conversations

The exhibition is the result of many years of planning: the Old Masters in the Picture Gallery are exposed to confrontational encounters that will catapult them from the seclusion of five millennia of art history and illustrate their relevance for today. For the first time ever, they will team up with works produced by non-European artists in modern media such as photography, film and installations.

These 19 fascinating encounters involve visitors and introduce them to the history of ideas spanning several millennia.

Anguissola – Claude Cahun

Sofonisba Anguissola – Sofonisba Anguissola was born in Cremona c.1531–35; she and her five sisters were trained as painters and encouraged by their father to develop their careers. A highly perceptive and sensitive portrait painter, she quickly became one of the period’s most famous female artists. She was court painter to King Philip II of Spain, and hosted artists, scholars and men-of-letters at her house in Genoa. She spent her final years at Palermo, where van Dyck drew a portrait of her shortly before she died in 1623.

Claude Cahun – Claude Cahun was born in Nantes in 1894 as Lucy Schwob. Active as a writer and photographer, she and her stepsister and partner, Suzanne Malherbe, hosted artists’ salons in Paris and befriended André Breton and the Surrealists. Throughout her life she fought for freedom of thought and the emancipation of women. Her resistance to the German occupation led to a ten-month incarceration by the Gestapo and the destruction of much of her work. In 1937, she settled in Jersey. Following the Nazi occupation of the island, Cahun became an active member of the resistance movement. She died in 1954

Bronzino – Lucian Freud

Agnolo Bronzino – Born in Monticelli near Florence in 1502, Angelo Bronzino trained in the workshop of Jacopo Pontormo; the two artists became life-long friends, and collaborated on what would be Bronzino’s earliest commissions for the Medici. In 1540, he became court painter to Cosimo de Medici. His idiosyncratic mannerist idiom was informed by the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, and his cool palette and distorted figures were meant to express internal tensions. In his portraits, Bronzino achieved a succinct individualization that reflects contemporary court etiquette. He died in Monticelli in 1563.

Lucian Freud – Lucian Freud, the grandson of Sigmund Freud, was born in Berlin in 1922. In 1933, his family emigrated to England and he trained as an artist in London. At the onset of his career Freud focused more on graphic media but then turned increasingly to painting. His authentic, unadorned and intimate nudes feature a novel rough handling that combines impasto brushwork and a sombre earthy palette. During a career that spanned more than seven decades, Freud produced a body of work that continues to reverberate today. Freud died in London in 2011.

Bruegel – Peter Doig

Pieter Bruegel d. Ä. – Pieter Bruegel the Elder was born in the village of Brueghel near Breda in 1525/30. Only around forty paintings by him have survived, twelve of which are now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum – by far the largest collection of his work in the world. Pieter Bruegel’s earliest undisputed works are landscapes; at the beginning of his career he also produced miniature-like paintings that focus on the topos of the looking-glass world. His oeuvre comprises both rustic scenes and depictions of boundary experiences of human existence. All his compositions feature a moralizing message. Pieter Bruegel’s idiosyncratic and fearless manner continued to fascinate posterity long after he died in 1569.

Peter Doig – Peter Doig was born in Edinburgh in 1959. His family moved many times while he was growing up and he lived, among other places, in Trinidad and Canada. In 1979, he settled in London where he trained as an artist. His landscapes feature unusual colour combinations and viewpoints. His compositions are marked by a sense of magical realism, which he uses to capture timeless moments and mysterious utopias on canvas. Today Peter Doig lives and works in Trinidad; he has been teaching at the Academy of Fine Art in Dusseldorf since 2005.

Brueghel – Steve McQueen

Jan Brueghel d. Ä. – Jan Brueghel the Elder was born in Brussels in 1568; he first trained with his grandmother, Marie Bessemers. An accomplished miniaturist herself, she laid the foundations for his sumptuous and fastidious flower still-lifes. But Jan Brueghel also adopted subjects from the works of his father, Pieter Bruegel the Elder: landscapes with mythological or biblical stories, as well as peasant scenes in rural settings. After an Italian sojourn lasting several years, he became – like Peter Paul Rubens a few years later – court painter to Archduke Albert VII of Austria, regent of the Spanish Netherlands. Jan Brueghel died in Antwerp in 1625 from complications of cholera.

Steve McQueen – Born in London in 1969, Steve McQueen is regarded as one of Britain’s most successful contemporary artists and film directors. He initially studied art and design in London but began to focus on films after moving to New York University’s Tisch School of Art. He was soon known for his video works and silent films shot in black and white. In 1999, McQueen received the prestigious Turner Prize for his photographs and installations. In his powerful and expressive films he tackles socio-critical topics. In 2014, he won an Oscar for the historical drama 12 Years a Slave.

Caravaggio – Franz West

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio – Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was born near Milan in 1573. His early works – which include the first still-life in Western art – are already marked by strong colours, dramatic effects of light and shadow, and a systematic reduction of figures to focus on the main protagonists. After completing his training, Caravaggio moved to Rome in 1590, where he continued to sharpen the realism already inherent in his early works. Accused of having killed an opponent in a brawl, Caravaggio spent the years between 1606 and his death in 1610 restlessly moving around Italy. The remarkable drama of his compositions and his use of lighting influenced seventeenth-century European painters as well as numerous photographers, painters and film directors in the twentieth and twenty-first century.

Franz West – Born in Vienna in 1947, Franz West studied with Bruno Gironcoli at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. His multifaceted oeuvre includes sculptures made of a variety of different materials such as plaster or metal, as well as graphic works and performances. In 1987, he began to produce works intended for sitting and lying down that focus on the boundary between artefact and quotidian object, thus forming a bridge between art and reality. From 1992 until 1994 West taught at the Städelschule in Frankfurt/Main. In 2001, he received the Golden Lion for his life’s work at the Venice Biennale. Franz West died in Vienna in 2012.

Correggio – Birgit Jürgenssen

Antonio Allegri, gen. Il Correggio – Born in Correggio around 1489 – and later named after his hometown –, Antonio Allegri was initially influenced by Northern Italian painting and the works of Andrea Mantegna. Soon, however, he evolved his own idiom marked by a delicate palette and an atmospheric softness. His religious compositions radiate a sublime intimacy and grace, while his mythological scenes are distinguished by a subtle sensuality. Correggio produced not only paintings but also church frescoes in which dramatic foreshortenings and the sophisticated organization of light create a perfect illusion of space and depth. He died in 1534.

Birgit Jürgenssen – Birgit Jürgenssen was born in Vienna in 1949 and studied graphics with Franz Herberth at the Academy of Applied Arts. After graduating she began to focus on photography. In her work, she questioned clichés of femininity, contrasting them with new concepts. She critiqued the dominance of men in the art world and campaigned for the recognition of female artists. She was the first to teach photography at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna, a position she held for over two decades until her death in 2003.

Giorgione – Nusra Latif Qureshi

Giorgio da Castelfranco, gen. Giorgione – Giorgione was born in Castelfranco, Veneto around 1477. A lack of signatures and the frequent involvement of other artists mean we can only attribute a small number of paintings to him. His early works are informed by both Italian and Northern painting; he soon evolved his own manner which is characterized by a warm palette and a poetic depiction of light, and his compositions depict man in harmony with nature. He died young in 1510, but as the teacher of Titian he and his work helped cement the leading position of Venetian painting in European art.

Nusra Latif Qureshi – Nusra Latif Qureshi was born in Lahore in Pakistan in 1973. She studied at the city’s National College of Arts and trained in the traditional art of Mogul miniature painting. In 2001, she emigrated to Melbourne to continue her studies and refine traditional painting techniques. In her work, which comprises paintings as well as installations and multi-media works, she focuses not only on the history of Southeast Asia but also on questions of how history and identity are constituted. She lives and works in Melbourne.

Lombardo – Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Tullio Lombardo – Tullio Lombardo, the Italian architect and sculptor, was born in Venice in 1455. Both he and his brother, Antonio, were employed in the workshop of their father, Pietro Lombardo, who as one of the architects responsible for the Doge’s Palace made important contributions to Early Renaissance art in Venice. Tullio Lombardo developed his very own, unique manner, producing classically infused sculptures marked by idealized and delicate proportions. He died in 1532.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres – Felix Gonzalez-Torres was born in Cuba in 1957; in 1979, he moved to New York to study at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. His first solo exhibition, held at the Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York in 1990, was followed by some notable early successes outside the United States. He is best known for installations comprising everyday objects like sweets, light bulbs, or clocks, some of which invite visitors to interact with them. His often minimalist compositions focus on subjects such as love, loss and sexuality, and are informed by his experience of HIV/AIDS, from which he died in 1996.

Rembrandt – Mark Rothko

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn – Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn was born in Leiden in 1606. After training for a few months with the history painter Pieter Lastman, he opened his first studio in his hometown in 1625. His early history paintings quickly brought him success and he moved to Amsterdam, where he mainly worked as a portrait painter. Both his humane, authentic likenesses of individual sitters and his narrative group portraits proved highly innovate contributions to the genre. His oeuvre comprises numerous self-portraits that chronicle his physical and emotional state until shortly before his death in 1669.

Mark Rothko – Mark Rothko was born in Latvia in 1903; in 1913, his family moved to the United States. He eventually settled in New York, where he produced his first representational-expressionist compositions, many of which were informed by Surrealism. Around 1949 a transition in his work led him to his mature style: paintings composed of carefully differentiated chromatic forms, objects of contemplation that demanded the viewers complete absorption. Rothko died in 1970.

Rembrandt – Fiona Tan

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn – Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn was born in Leiden in 1606. After training for a few months with the history painter Pieter Lastman, he opened his first studio in his hometown in 1625. His early history paintings quickly brought him success and he moved to Amsterdam, where he mainly worked as a portrait painter. Both his humane, authentic likenesses of individual sitters and his narrative group portraits proved highly innovate contributions to the genre. His oeuvre comprises numerous self-portraits that chronicle his physical and emotional state until shortly before his death in 1669.

Fiona Tan – Fiona Tan was born in Pekanbaru (Indonesia) in 1966. She grew up in Australia before moving with her family to Amsterdam, where she began to train as an artist in 1988. Tan’s oeuvre comprises photography and video works as well as complex spatial installations in which visual images, words and sounds are conflated to produce a coherent single whole. A seminal topic in all her work is the construction and fluidity of memory, time and identity. Tan’s sensual, tangible creations question established concepts of time and memory, reality and fiction.

Roman Antiquity – Eleanor Antin

Roman Antiquity – For this exhibition, Antin’s work has been placed alongside a classical sculpture of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty.

Eleanor Antin – Eleanor Antin was born in New York City in 1935, and studied acting and creative writing there in the mid-1950s. Her oeuvre comprises video works and photography as well as installations and performances. In her works, she immerses herself in the past – from ancient Rome to her own Jewish heritage – in order to define it from a modern viewpoint; they often deal with socio-critical, political and feminist subjects in a humorous way. In 1975, Antin was appointed (now emeritus) professor at the University of California San Diego (UCSD).

Roman Antiquity – Paul Cézanne

Roman Antiquity – Over the course of his life, from student to old age, Cézanne filled sketchbook after sketchbook with drawings made directly from the Louvre’s collection of classical Greek masterpieces and their Roman copies.

Paul Cézanne – Paul Cézanne was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839. He moved to Paris in 1861 and enrolled at the Académie Suisse. He made regular visits to the Louvre to study Old Masters, and their works inspired his earliest paintings. He achieved a remarkable degree of autonomy in his colours and forms, which he charged with constructing and organizing his compositions. In 1870, he began to focus on landscapes, eventually evolving a modulation of hues in which clearly separated dabs of colours are placed next to each other. His ultimate manner – i.e., the works he produced in the years prior his death in 1906 – is characterized by a consolidation of the pictorial structure and a heightening of chromatic intensity.

Rubens – Maria Lassnig

Peter Paul Rubens – Peter Paul Rubens was born in Siegen in Westphalia in 1577. Following the death of his father, the family moved back to Antwerp in 1589. There, Rubens trained as a painter. After travelling and studying in Italy for several years, he returned to Antwerp; in 1609 he became court painter to Archduke Albert VII, who was much impressed by Rubens’ sensual and dramatic compositions. In 1622, Rubens undertook his first diplomatic missions to France, Spain and England; in 1630 he was knighted by King Charles I. That same year, Rubens married his second wife, Helena Fourment, who clearly represented his ideal of beauty and whom he frequently painted in his later works; he died in 1640.

Maria Lassnig – Maria Lassnig was born in Carinthia in 1919. Shortly after completing her training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, she produced the first of her paintings and drawings focusing on depicting the emotions of her body; her theory of »body awareness« would go on to inform her entire oeuvre. After sojourns in Paris and New York she returned

to Vienna in 1980 and was appointed professor of painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1982, she founded Austria’s sole teaching studio for animated filmmaking. Late in her career, she was honoured with numerous international exhibitions and received countless prizes, among them a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Lassnig died in 2014.

Santvoort – Catherine Opie

Dirck Dircksz. Santvoort – Dirck Dircksz. Santvoort was born in Amsterdam in 1610. He presumably trained with his father, the painter Dirck Pietersz. Bonepaert. He was deeply influenced by the work of Rembrandt and may even have been his pupil. Sandvoort soon became known for his elegant and restrained portraits. Particularly popular were his portraits of children, in which he combined his power of observation with restrained handling to harmonious effect. Sandvoort died in his hometown in 1680.

Catherine Opie – Catherine Opie was born in Ohio in 1961. She completed her artistic training at the California Institute of the Arts in 1988. Her photographic oeuvre comprises studio portraits, landscapes and urban spaces. She is best known for her provocative portraits in which she questions concepts of social, sexual and cultural identity. In her works, she never abandons a sense of formal rigidity, combining elements of historical portraiture with a determinedly contemporary atmosphere. Opie lives and works in Los Angeles, where she is Professor of Photography at UCLA.

Tintoretto – Kerry James Marshall

Jacopo Robusti, known as Tintoretto – Born in Venice in 1518, Jacopo Robusti, called Tintoretto, was raised in an environment dominated by harmony and colour. In his paintings he favoured dramatic compositions, sophisticated lighting and a strong illusion of depth. From 1565 onwards, Tintoretto produced his masterpiece, a large number of paintings for the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice that is today one of the most important extant religious pictorial cycles.

Produced shortly before his death in 1594, his final works are highly dramatic and feature chromatic light reflexes; they were much admired in the nineteenth century by the Impressionists and their successors.

Kerry James Marshall – Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955, Kerry James Marshall is strongly influenced by both his childhood in the Deep South and his training at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, where he witnessed the Black Panther Movement. From painting to sculpture to photography and video installation, his oeuvre represents an intense examination of the history of black identity in America and in Western art. In his paintings, which alternate between abstraction and the use of comic-book aesthetics, Marshall looks at subjects often excluded from the artistic canon. He lives and works in Chicago.

Titian – Pablo Picasso

Tiziano Vecellio, known as Titian – Born in the Veneto in 1488/90, Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian, trained with the leading masters of the Venetian Renaissance. This helped him to quickly develop his own chromatic manner, which continued to influence generations of later artists, especially portrait painters. His early works are marked by a strong sense of drama, but around 1530 his compositions become calmer. In his late works the elegance and beautiful palette of his earlier manner are replaced by an intense feeling for colour. Until his death in 1576, Titian worked for a number of important Italian princes and the House of Habsburg.

Pablo Picasso – Born in Málaga in 1881, Pablo Picasso first moved to Paris in 1900. The works he produced during his Blue and Rose Periods and his seminal role in the development of Cubism were but the beginning of an exceptional artistic career. His extensive oeuvre, which numbers around 50,000 artworks in total, comprises paintings, drawings, prints, collages, sculptures and pottery. The Picasso Museum in Barcelona was opened shortly before his death in 1973, and his work has been celebrated in countless important retrospective exhibitions.

Titian – Joseph Mallord William Turner

Tiziano Vecellio, known as Titian – Born in the Veneto in 1488/90, Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian, trained with the leading masters of the Venetian Renaissance. This helped him to quickly develop his own chromatic manner, which continued to influence generations of later artists, especially portrait painters. His early works are marked by a strong sense of drama, but around 1530 his compositions become calmer. In his late works the elegance and beautiful palette of his earlier manner are replaced by an intense feeling for colour. Until his death in 1576, Titian worked for a number of important Italian princes and the House of Habsburg.

Joseph Mallord William Turner – J.M.W. Turner was born in London in 1775, and the British landscape forms the central theme of his early works. His paintings are informed by his many European journeys, which also introduced him to Venetian colourism, which deeply impacted his style. Turner’s compositions combine a lively colourfulness and an atmospheric overall effect in what appear to be spontaneous snap-shots, making him a precursor of the Impressionists and modern art in general. In addition to his paintings he also published theoretical treatises and served on the board of the Royal Academy. J.M.W Turner died in London in 1851.

Van der Weyden – Ron Mueck

Rogier van der Weyden – Rogier van der Weyden was born in the Flemish city of Tournai around 1400. He trained with Robert Campin before moving to Brussels, where he lived and worked until his death in 1464. We know only very little about his early work, but it probably reflected the influence of a teacher such as Jan van Eyck. In 1540, van der Weyden travelled to Rome, where he developed a new pictorial concept. He overcame the planar compositions of his precursors and began to compose his figures in a more plastic manner, even if their spatial expansiveness remains somewhat limited. Today, he is regarded as the most important representative of fifteenth-century Netherlandish painting after Jan van Eyck.

Ron Mueck – Born in Melbourne in 1958 into a family of German doll-makers, Ron Mueck was familiar with different artistic techniques from an early age. In 1983, he moved to London where he produced models for film sets, TV productions and advertisements, including for Sesame Street and The Muppet Show. In the 1990s, Mueck began to work full-time as an artist. His hyper-realistic sculptures of people made of fibreglass and silicone seem to address the viewer directly, yet his play with scale results in a distortion that questions our perception.

Velazquez – Édouard Manet

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez – Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez was born in Seville in 1599. Shortly after completing his apprenticeship, he opened his first workshop; in 1623, he entered the service of King Philip IV of Spain and moved to Madrid with his young family. Velázquez mainly produced portraits of members of the court and the royal family; in 1659, a year before he died, he was knighted by the king. In his works he evolved a radically novel way of depicting colour and light that would become a key influence on the art of Manet and the Impressionists.

Édouard Manet – Édouard Manet was born in Paris in 1832 and trained with the history painter Thomas Couture. As a young student, he began to visit the Louvre to study Old Master paintings, and despite his flat and realistic manner his art was always deeply informed by tradition. Hence even scandalous paintings like his Le Dejeuener sur l’Herbe or Olympia can be traced back to classical models. In their unconventional realism, Manet’s compositions often visualized conflicts or tensions, and he did not receive official recognition until the years before his death in 1883.

Visitors from all over the world

The many different works paired with our Old Masters have heterogeneous provenances. »The Shape of Time« brings together loans from the world’s most renowned museums. We are showing works from the Tate Gallery, London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Musée Picasse, Paris, The Art Institute of Chicago, The British Museum, London, the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Connecticut as well as important private collections.

We look forward to seeing you!

Save the Date

Talks with the artists

Not only artworks but also the artists who produced them engage in conversations. In this series of talks, curator Jasper Sharp welcomes selected artists for a public conversation at the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Monday, 26.3.2018, 7 p. m.

Catherine Opie

Monday, 16.4.2018, 7 p. m.

Fiona Tan

Monday, 14.5.2018, 7 p. m.

Kerry James Marshall

Monday, 25.6.2018, 7 p. m.

Steve McQueen

Seats are limited so please register at talks@khm.at.